* * * *

My dad and I were in the car one day –

I don't remember how old I was, but I do know I was a legal adult for

what it's worth – and he flipped on the country music station. I

hated country music, so I protested.

“You know, Kevin,” he said,

“everyone goes country at some point.”

At that point I merely took it to mean

that I was doomed to a later life of listening to the Toby Keiths and

Taylor Swifts of the world. But as I've grown older it occurred to me

what he meant: People get old, and as they get old they get more

conservative not just in their politics but in their way of life.

Things get simpler, and simplicity and directness of country music is

the perfect soundtrack for one's twilight years.

Needless to say I'm not old (yet), so I

don't listen to country music. Well, I don't listen to modern

country music. That music is just pop music with twang; a celebration

of guns and God, pickup trucks and patriots.

Little did I know, though, that there

would be country music that appealed to me, and that I would find it

in the unlikeliest of places.

* * * *

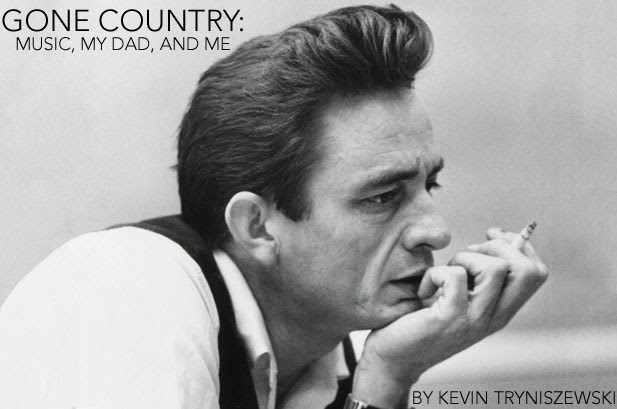

It was 2003, and Johnny Cash had

recently released an album full of mostly cover songs, and the lead

single was “Hurt,” a song written in 1994 by one of my favorite

artists – Nine Inch Nails. Because of this fact, I had to hear it.

At first I was flummoxed by the song, not knowing how to feel about a

dying old man singing a song originally made by an artist I

considered vital. But then I listened to the rest of the album,

intrigued by its haunting, morbid beauty.

Then, Johnny Cash died. All at once it

both ended and began.

I downloaded an “Essentials” Johnny

Cash album. Dopey college-kid me was endlessly amused by the line

from “Sunday Morning Coming Down”: “The beer I had for

breakfast wasn't bad, so I had one more for dessert.” I watched all

the retrospectives of his life on television, which made me feel like

I knew the man before I knew the music. It was at that point that I

started my way down the wormhole – or is it fishin' hole? – of

classic country music.

My journey into country music took some

time. I've listened to countless songs and have read an armload of

books on the subject. Looking over the artists that have sustained my

interest in the genre, it has become pretty clear that they all have

one thing in common.

They are the ones who have withstood

the test of time – the ageless and the immortals – the ones who

are so respected and so well-known that many know them by just their

first names: Hank, Johnny, Willie, and Waylon. (And some by their

last names, such as Haggard and Kristofferson.) To a man, they all

shared a distinct distaste for the Nashville music machine that

chewed up and spat out country music stars like spent wads of

tobacco.

All of those men had their own artistic

visions that didn't always fit in with what the industry wanted. Hank

Williams wanted to keep it simple, but also wanted to write his own

songs. Johnny Cash wrote about a multitude of things, but the

subjects he cared most deeply about – his faith, the downtrodden,

the workingman, American Indians – were also the least likely to

sell records. He recorded those songs anyway, and his legacy is

better for it. Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings believed that both

rednecks and hippies could come together and enjoy the same music –

and they were right. Kris Kristofferson couldn't sing or play worth a

lick, but had such a way with words that some think he was country

music's answer to Bob Dylan.

Beyond the directness and simplicity of

their music – something inherent in all country music – these

guys lived their songs and meant the words that they sang. They wrote

the type of music that you can feel in your guts yet still resonates

with your brain. From “Lost Highway” to “Man in Black” to

“Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground” to “Sunday Morning

Coming Down,” these men have written classics that have informed my

outlook on life. All the heartbreak and loss and despair isn't

pretty, but it is life.

Of course, the music is of most

importance, but the men behind the music is also of interest. And

this is where my dad comes back into the story.

* * * *

I can't claim to know all that much

about my dad. But I have seen pictures and have heard stories (some

of them over and over and over again, like that one time he saw the

Stones and the Eagles, and the Eagles were way better). He had long

hair in the 70's and listened to the Beatles and Pink Floyd. He did

drugs. (I have no proof of this, mind you, but it was the 1970's.

Everyone did drugs then. How else do you explain the fashion

and the music?) None of that is terribly interesting, I know, except

for maybe that my twenties were pretty similar to his.

But there is one thing from that time

period that has always stuck with me. It comes from a half-heard

conversation some years ago – there was probably alcohol involved –

about the Vietnam War. Essentially the war ended and the draft was

discontinued right as my dad was graduating high school. He regretted

not being able to serve his country. That in and of itself was fine,

but I've come to think of it as more than just patriotism. I think,

deep down inside, he supported the war. And though that kills my

somewhat liberal (but mostly centrist) heart, it's also kind of

subversive in a weird way. Here you have a kid with long hair, full

of Dark Side of the Moon and Dylan and god knows what else,

ready to go halfway across the world to fight for an establishment

that probably couldn't care less about him.

That subversion makes me proud. It is

also part of what drew me to certain country stars. Johnny Cash

insisted on having black musicians on his television show even though

race relations were, to put it mildly, not good. Willie Nelson

flaunted his hippie bona fides – the long braided hair and love of

pot – but also wrote songs that made you actually feel your

feelings when it wasn't popular in country music to do so.

* * * *

My dad is a flawed human being; a

jumble of clashing ideals. He supports unions but votes Republican.

He believes in God but doesn't go to church. He's been smoking since

he was a teenager but told me not to smoke. I cannot attack these

things not only because he's my father or because I am also flawed,

but because the flaws and imperfections fascinate me. I could get

cute and call it the family tradition, but I think it's the human

tradition. Aside from empathy, I think imperfection is our defining

trait.

* * * *

When putting this piece together in my

head, I came to my conclusion first and tried to connect the dots

second. The relationship I have with my dad and country music isn't

terribly complex, but it also isn't the easiest to put into words.

After some hours of thinking about it,

I discovered that everything centered on one point. All of my

favorite country stars had singular artistic visions, producers and

record labels be damned. They lived life and performed music on their

own terms.

My dad never had a father growing up,

so when I was born he had to forge his own road of fatherhood. If

there's anything I can take away from growing up on that road, it is

that I should be an individual, that I have to forge my own road if I

want to make anything of this life.

He couldn't hold my hand all the way

down the road, of course, but he could give me some tools to help. He

taught me to be intellectually curious, to always ask questions and

to be wary of authority. (Not to be confused with saying all

authority is bad, which is another argument for another day) He

encouraged me to be great at everything, whether it was school or

sports or writing or girls. He gave me advice whether I sought it or

not. He was genuinely sad when he couldn't help me. Perhaps, most

importantly, he showed that it was okay to have feelings and to

express them no matter what they are.

Maybe this just sounds like a checklist

on how to be a good parent. And maybe he checked all those things off

and maybe I just failed to execute some of them. But I don't think

that's really the point. I think all along he wasn't just teaching me

how to be a man or even how to one day be a father; he was teaching

me how to be a well-rounded, decent human being.

* * * *

As fathers sometimes are, my dad was

right this time. I – to use some redneck parlance – done gone

country. Ironically, we've never really bonded over country music the

way we did over the Beatles goofy comedy movies. Or did we?

It's true, my dad didn't exactly show

me country music. I discovered it mostly on my own. I also fell in

love with more current country and folk artists, such as Sturgill Simpson and The Avett Brothers. In some strange way, I found both

myself and my father in the music. Neither of us may be genius

songwriters (or pill-popping, womanizing drunkards, for that matter)

but I think there's a rebel spirit in both of us, and I think of that

and our relationship when I listen to the music.

It may have been unintentional, maybe

not, but think either way my dad would be proud at what I learned in

thinking about all of this: Sometimes the best lessons you can learn

aren't the ones passed down from generation to generation, but the

ones you learn on your own.

No comments:

Post a Comment